Long before the formation of political organizations serving the liberation movement of Palestine, resistance was and continues to be seen in the form of a piece of clothing – the Keffiyeh.

The Keffiyeh illuminates the history of Palestinian resilience, serving as both a symbolic and physical tool of resistance. During the British Mandate, especially during the 1936-1939 Arab Revolt, Palestinians rebelled against the British in Palestine. They used the keffiyeh to conceal their faces and avoid capture. The widespread adoption of this practice contributed to their success in achieving their goals, even in the face of the British authorities’ attempts to ban it.

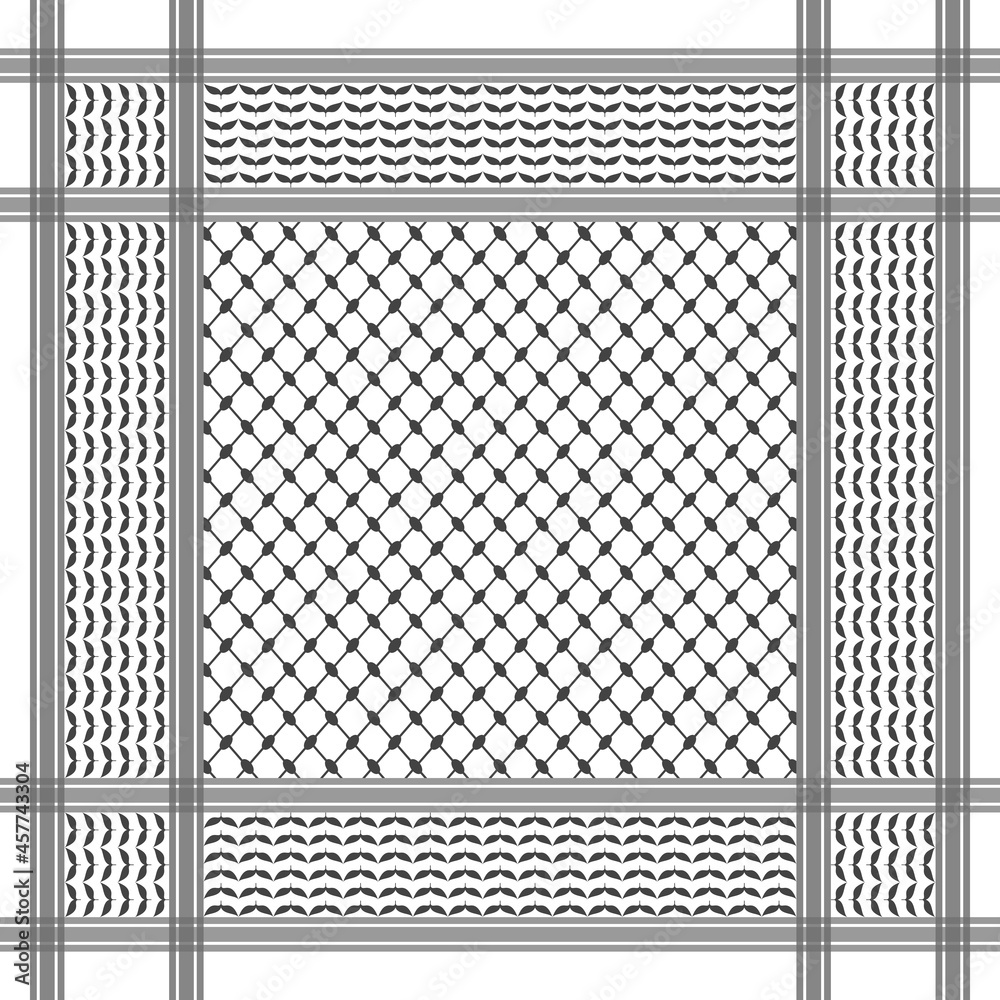

The keffiyeh is a traditional piece of headdress worn by Arabs as a tool of protection against the sandy weather which then evolved into a black and white chequered piece with distinctive embroidery style that represents conformity and patronage with Palestinian solidarity all over the world.

It has been almost four months of continuous Israeli bombing and airstrikes in Gaza. This has sparked global outrage, and students across Education City have made wearing the Keffiyeh a part of their outfit exemplifying their solidarity for Palestine. For Hamad Abu Hassan, the junior manager for the Students for Justice in Palestine club at NU-Q, It didn’t matter as much who was wearing it as how many.

“When I see them (other students) wearing their Keffiyeh, it just reminds me that we’ll never be erased, that we will hold on to our culture and our history for as long as the occupation exists,” says Hassan.

On an individual level, Hassan adds that being a Palestinian in the diaspora, the Keffiyeh is a symbol that carries connotations far beyond a mere piece of cloth “Wearing my Keffiyeh is my way of resisting the occupation. It’s my way of telling them that my identity will not be erased.”

Tatreez is referred to as Palestinian embroidery, employed by Palestinians to preserve their culture. The colorful thread that proceeds the stitch brings with it a story. “It is one of the main ways Palestinian women take part in resistance” notes Zeina Al Qawasmi, Vice President of the Justice in Palestine club at NU-Q. Taking part in this resistance is not only through the hands of the embroiders though, and a paragon of this is Zeina’s rich collection of delicate handmade Tatreez. She adds, “This collection is my pride and joy, it makes me feel connected to home even when I’ve never been.” It includes traditional long gowns (thobes) that are symbols of Palestinian women and the National dress.

In an era of fast fashion, there is a thin line between fashion serving as a utilitarian or stylistic choice. Fashion has many purposes and the Keffiyeh prompts reflection on one of its utilities which is politics. Choices, designs, colors, and fabrics are all representations of underlying economic, social, or political history. The Keffiyeh has an embroidered element to it and it speaks to the importance and value the art of embroidery holds in Palestine. Women found themselves to be struggling economically and financially after the Nakba in 1948 which expelled Palestinians from their homes.

A dominant female hobby, women embroiderers found themselves opening embroidery studios to support their families and themselves. Drawing from the utility, the style of the Keffiyah relies on purposes broader than the aesthetic choices of the embroiderers.

A major component of the design includes a hand-embroidered black fishnet pattern contrasting against the main cloth.

This pattern represents the Palestinian fishermen and sea: an indispensable part of Palestinian economic and cultural history. This delicate fishnet on the Keffiyeh is a symbol of the hands of Palestinian resilience that weaved a tool for self-sustainability during economic and political instability. The fishnet pattern is then separated by a thick dark vertical line with two white parallel lines: resembling a road. This stylistic choice is called Bold, representing the trade routes going through Palestine. Palestinian trade routes made possible the exchange of goods to many geographical locations between Europe, Asia, and Africa. This road embodies the journey of Palestinians: a journey of grit and struggle.

Remembering his family’s roots in Palestine, Hassan narrates “My grandfather was around three or four years old and my grandmother was an infant when they were kicked out of Palestine.” Their journey as Palestinians in the diaspora took them from Palestine to Jordan, then to Saudi Arabia, and ultimately to Qatar, where Hamad’s family has settled to this day. This symbolic road on the Keffiyeh doesn’t only connect trade routes, but also the Palestinians- who despite being displaced from their homeland- continue to nourish their love for the distant soil of their birth. “Seeing my parents and their parents hold on to their love of the country that they were born in, even after they’ve grown old, 75 years after being displaced, living an entire life outside of Palestine reminds me that love for Palestine never fades,” said Hassan. It is rather a journey that is continued and will continue through being passed on to the new generations. Thirdly, the sea wave pattern on the Keffiyeh represents the deep connection to the land and the Mediterranean Sea; an integral part of Palestinian embroidery and history.

The intricate Stitches of Tatreez have geographical roots; mapping different cities and unique stories through colorful threads. These motifs- that look geometrical in shape- acknowledge more than the artistry of the embroider, it represents their identity through impressions of the daily surroundings of a maker’s geographic location. Qawasmi adds, “My stitches are specific to Hebron, the city I’m from.” Owning and appreciating the Palestinian embroidery includes acknowledging its’ roots and significance, as it serves as an indicator between those who normalize the occupation and those who oppose it. In the context of non-Palestenians wearing the Keffiyeh, it is important, Hamad adds, “If (people) are wearing it because it just looks good, but they’re not advocating for Palestinian rights, they’re not supporting the Palestinian cause, then it’s just inappropriate.”

Luxury brands like Cecile Copenhagen have commercialized the Keffiyeh by designing clothing items like shirts, pants, and lingerie with a similar design.

In an interview with The Guardian, Palestinian fashion designer Omar Joseph Nasser-Khoury disses this act with a claim that it normalizes the occupation. Highlighting the importance of Keffiyeh, Khoury adds “It’s almost disrespectful and it’s exploitative” for luxury brands to use this as a style element. In a conversation regarding this design with an Israeli designer Dorit Bar Or. Hassan, Khoury adds “You have people who were dispossessed in 1948 and made refugees and they still live in camps in Lebanon and then you use this garment, which carries all that pain, for personal advancement.”

A pillar of knowing your Keffiyeh is inquiring about its manufacture and where you get it from. Hirabwi is the last Palestinian factory that is still making the original Keffiyeh in Palestine. They have options for pre-orders and global shipping, which could be one’s source of getting first-hand embroidered keffiyeh made in Palestine.

“I need to buy more keffiyeh from Palestine specifically to feel a stronger connection, a connection to my homeland that my parents or I have never been to, that my grandparents were kicked out of,” Hassan adds, “It’s a symbol of unity and resilience.”