The hot topic of today, generative artificial intelligence, performs most smoothly in Western languages and cultural contexts, and the reasons are clear. More than 90 percent of the data used to train large AI models originates from English sources. As a result, speakers of less dominant languages often face slower responses, weaker accuracy, or even apparent mistakes. This imbalance points to a larger concern: beyond issues of access and equity, it undermines the credibility of the technology itself.

At Northwestern University in Qatar (NU-Q), students quickly notice the gap. When they turn to ChatGPT in English, the answers often come back clear, detailed, and authoritative. But switch to Kazakh, Arabic, or Chinese, and the responses slow down, blur into vagueness, or miss the mark entirely. For these students, it isn’t just a technical glitch; it’s a blow to their trust in artificial intelligence.

Amina Aktailakova, a student from Kazakhstan, recalls her own experience: when she posed a question in English, ChatGPT produced a clear and well-structured answer within seconds. But when she typed the very same question in Kazakh, the response lagged and was often off the mark. “If I want something reliable, I have no choice but to ask AI in English,” she said.

Aktailakova’s frustration is far from unique. Fatima Al Naemi, a student from Qatar, faced similar issues when she tried using AI tools in Arabic, especially when typing in local dialects. “The system often mixes them up,” she explained, “and sometimes gives answers that have nothing to do with my question.”

And the issue isn’t limited to regional dialects. A Chinese student, Fan Wu, found the experience even more ironic. When she asked about Chinese cities in Mandarin, the AI included Singapore in its response. “That kind of mistake would never happen in English,” she said with a sigh. “It’s astonishing that a tool that seems so powerful suddenly becomes so unreliable the moment you switch languages.”

For NU-Q students, the real issue isn’t the errors themselves—it’s the trust those errors erode. If simply switching languages can make a system stumble over the most basic questions, how much faith can anyone place in it? Their concern is echoed in a 2025 study by Aichner and colleagues from the South Tyrol Business School, published in the Journal of AI & Society: Knowledge, Culture and Communication, which argues that user trust in AI is never automatic; it depends on factors like accuracy, explainability, and cultural and linguistic alignment. Once those are missing, credibility quickly falls apart.

That question of trust extends beyond students. Professors at NU-Q are asking the same questions. Mohammed Ibahrine, a professor in residence, experimented with an alternative to ChatGPT: Deepseek AI, a large language model developed in China. He hoped a “non-Western” platform might address some of the biases and pay closer attention to underrepresented languages.

But he soon found its limits—responses in non-Chinese languages were still slow and often off the mark. “If you don’t have proficiency in Chinese,” he admitted, “you can’t really unlock the tool’s potential.” For Ibahrine, the experience made one thing clear: switching platforms doesn’t make the trust problem go away.

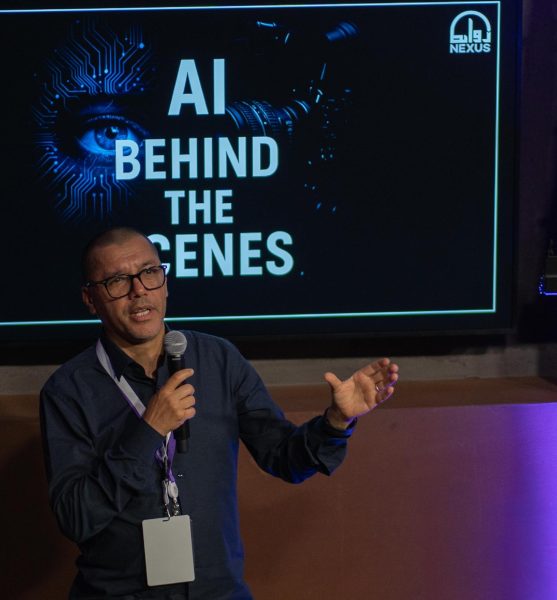

This credibility gap was taken up in greater depth at the AI RAWABET Conference, organized by the AI and Media Lab at NU-Q. Nigerian scholar Jake Okechukwu Effoduh pointed out that most modern AI training data comes from the Global North, which leaves Global South users more likely to encounter outputs that feel alien or unreliable. To illustrate, he offered two sharply contrasting African examples.

The first came from Nigeria, where a foreign exchange app could predict black market rates but failed to display the naira symbol. No matter how advanced the system’s math was, users lost confidence immediately. Without reflecting local realities, AI never stood a chance of being trusted.

His other example was a hopeful one. In parts of East Africa, traditional midwives began acting as “AI interpreters,” bridging the gap between health apps and community women. When apps issued confusing or even faulty alerts, the midwives would explain the results, reassure patients, and flag potential flaws. That human mediation helped restore credibility, turning AI into a genuinely useful tool.

Taken together, the two examples underscored Effoduh’s larger point: AI is not inherently trustworthy. Whether it earns trust depends on how well it respects local languages, cultures, and needs. A study by Afroogh and colleagues found that credibility does not come from increasingly complex algorithms, but rather from whether people can understand AI and recognize reflections of their own experiences within it. The East African case clearly demonstrates that AI can only truly earn trust when it incorporates both human factors and local contexts.

From NU-Q students’ doubts to their professor’s experiments to scholars’ critiques, one theme stands out: the real challenge for generative AI isn’t whether it can produce answers, but whether it can earn trust.

It is a fact that Western-built systems dominate, rooted in their vast resources and the global reach of English, and there is nothing inherently wrong with that. But if the Global South continues to be overlooked, the issue becomes not just bias, but a full-blown credibility crisis. At the same time, the Global South faces a different challenge: the pressure to build its own models and datasets to make its languages and perspectives visible in an AI landscape still dominated by the West.